The invention of photography

For his first experiments,

Niépce placed sheets of paper coated with silver salts on the back of a camera obscura. It was known that silver salts (silver chloride) darkened when exposed to light. In May 1816, he succeeded in capturing the first image of nature: a view from a window. It was a negative, but the image was not permanent. After opening the camera, the exposure process continued, causing the image to darken further until it eventually disappeared completely. Niépce called this process “Retina.” The recording method of the project “THE 7th DAY” is based on this technique. Disappointed by the inability to permanently fix this first photograph, Niépce turned to other methods.

In March 1817, he focused his attention on guaiac resin.

This yellow resin changes color from yellow to green when exposed to daylight and is only sparingly soluble in alcohol. This suggested the potential for permanent photographs. However, this property of the resin is triggered only by UV light. The glass lenses of his camera obscura largely filtered out this light, preventing the guaiac resin from changing its properties inside the camera. While contact copies in direct sunlight were possible, photographs taken with a camera obscura remained unattainable.

Disappointed, Niépce turned to other substances, particularly natural asphalt, also known as “Bitume de Judée.”

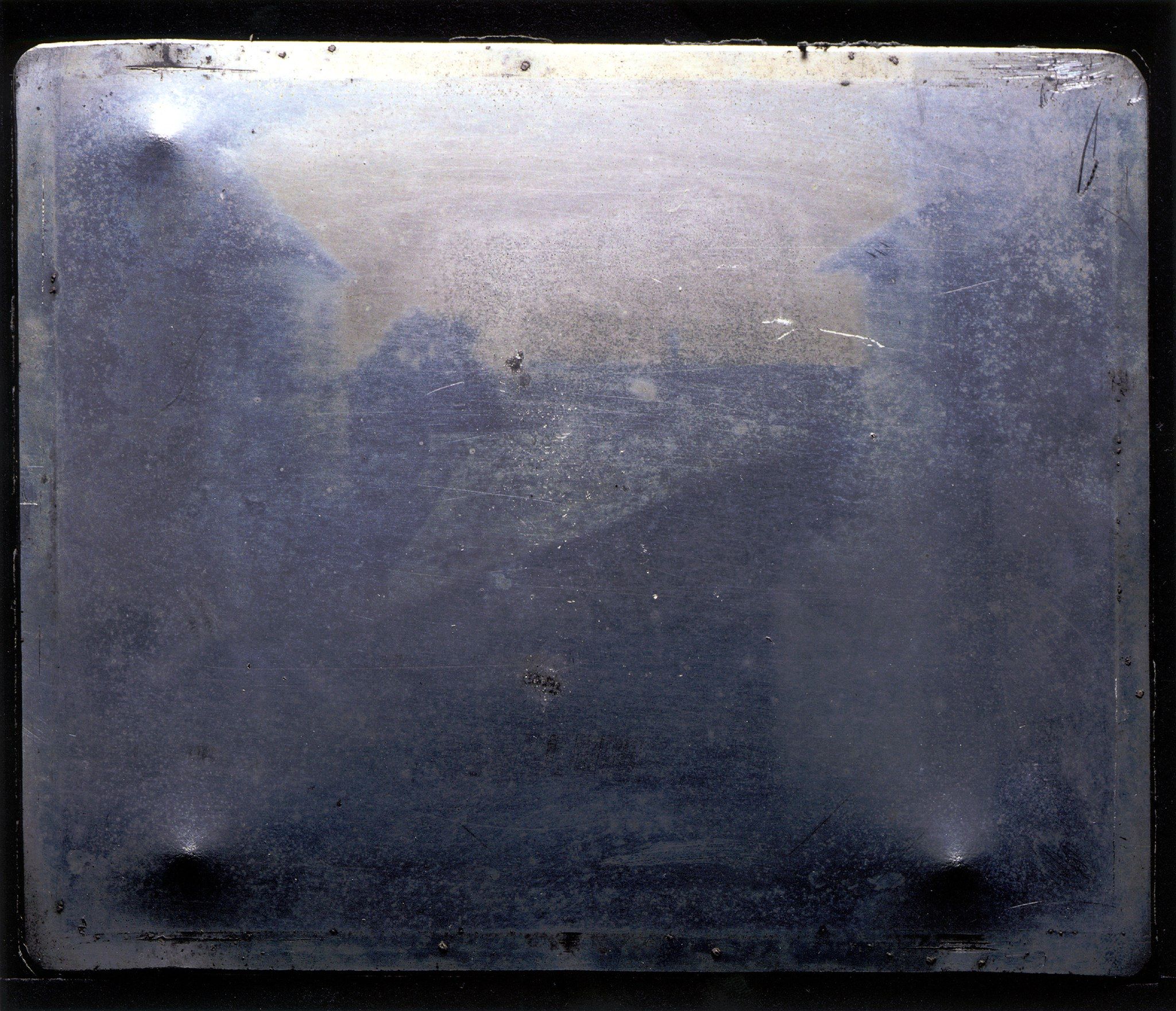

In France, this viscous, black-brown mineral was mined at locations such as the Mine du Parc near Seyssel, about 100 kilometers from his estate. The finely powdered natural asphalt was dissolved in lavender oil and thinly applied to metal plates (copper, tinplate), stone, or glass. After drying on a hot iron plate, the coated material could be exposed to light. The exposure time for contact prints took several hours in sunlight, and even several days in a camera obscura. Depending on the amount of light, the asphalt hardened to varying degrees. After exposure, the softer areas – those that received less light – could be washed out with a mixture of lavender oil and white oil. In his “Notice sur l’Héliographie,” Niépce describes this process in detail.

Although the invention of photography can be dated to 1824 based on Niépce’s letters,

the image that has survived to this day dates from 1827. The photographs Niépce took in 1824 have disappeared – likely because the expensive materials at the time were reused. On September 16, 1824, Nicéphore Niépce wrote to his brother Claude, who was living in England at the time:

“I am pleased to finally inform you that, thanks to the refinement of my methods, I have succeeded in obtaining a view as I had hoped for, although I scarcely dared to hope for it, as my results had so far been very incomplete. This view was taken from your room, which faces Le Gras; for this purpose, I used my largest camera obscura and my largest plate. The image of the objects is reproduced with astonishing clarity and fidelity, even down to the finest details and their subtlest shades. Since this contact print is almost untoned, its effect is best judged when the plate is viewed obliquely: then, through the shadows and light reflections, it becomes visible to the eye; and this effect, I must say, my dear friend, truly has something magical about it. (…) In the meantime, as of today, you can consider the success of applying my methods to views – whether on stone or glass – as a proven and indisputable fact.”

View from the Study of Le Gras

(French title: La cour du domaine du Gras – “The Courtyard of the Le Gras Estate” or Point de vue du Gras – “View of Le Gras”) is the first successfully captured and still-surviving photograph in the world. It was taken in 1827 by Joseph Nicéphore Niépce in Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France.

Przemek Zajfert, März 2025