From Heliography to AI-Generated Images

Przemek Zajfert, October 2024

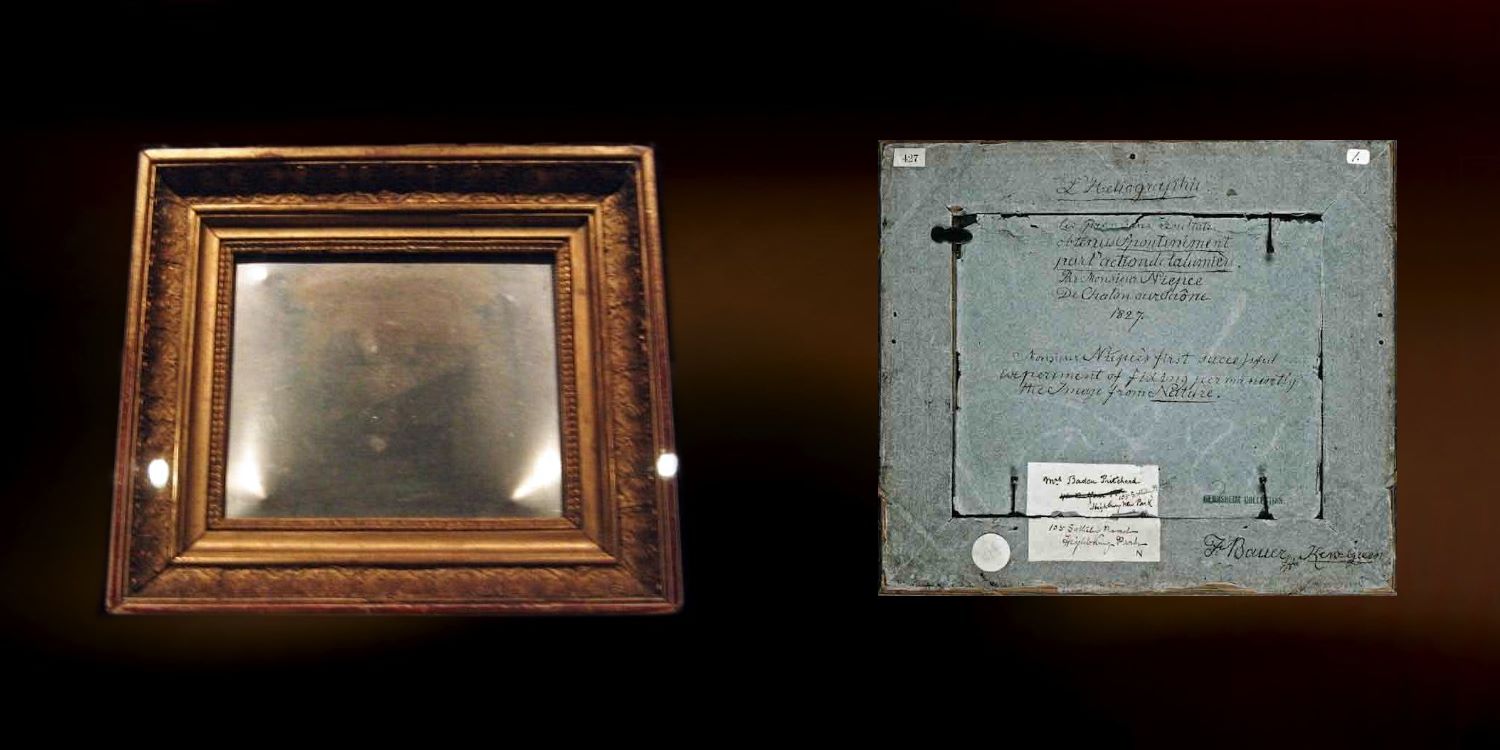

The Oldest Surviving Photograph in the World

In the late summer of 1827, after several days of exposure, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce held in his hands the oldest surviving photograph in the world – View from the Window at Le Gras (French: Point de vue du Gras). The image (16.5 × 21 cm) shows the view from the window of his studio in Le Gras (Saint-Loup-de-Varennes, France).

Niépce created the photograph using a camera obscura on a tin plate coated with natural asphalt dissolved in lavender oil. He called the process heliography – derived from the Greek for “drawn by the sun.” Although the procedure was laborious and time-consuming, it marked a turning point in human history: the first successful attempt to permanently capture a fleeting moment.

The resulting image, delicate and barely visible, was a quiet but revolutionary triumph over transience. With this technique, the previously intangible became tangible – fixed on metal, preserved, and transportable.

Google Street View

180 years after Niépce created the first photograph, in 2007, Google released the first images of its Street View project. Cameras mounted on cars, drones, and backpacks began documenting the world, creating a vast global archive of images. This technology functions almost autonomously – cameras capture reality while algorithms automatically catalog each individual frame. Today, hundreds of billions of images document our everyday lives, leaving a digital trace of the present.

The everyday captured by Google Street View, seen against the backdrop of asphalt, creates a multi-layered narrative in which every detail – a glance at a phone, a random shadow – begins to define space and time. Public space ceases to be mere scenery; it becomes a stage on which we, often unconsciously, act as participants shaping a shared identity.

Street View photographs are digital records of reality, yet their value lies in their connection to the material world – they document real places and moments and serve as a kind of imprint of reality. This aligns with Roland Barthes’ thesis that photography leaves a trace of the past and provides material proof of what once existed.

AI-Generated Images: The Dreams of a Digital Mind

Images generated by artificial intelligence, however, are an entirely different phenomenon. They do not arise from capturing a specific moment, but from algorithmic imagination – creations without a direct reference to reality. They resemble the dreams of a digital mind: abstract, detached from time and space. They lack the authenticity that comes from freezing a fleeting moment. Unlike photographs, which document reality, AI-generated images do not possess a punctum (Barthes) – that emotional spark that gives a photograph depth and a personal dimension.

The Magic of Images

In a time when images are predominantly digitally generated and consumed, I have often wondered whether they can preserve the same magic and value as the earliest photographs. Digital images are, by nature, eternal – stored as bits and bytes in the digital realm, free from time and its effects. Yet this immutability strips them of the human quality that made the first photographs so special.

I believe that images regain their original magic only through their physical form, exposed to the passage of time and the hardships of life. In their tangible incarnation, as carriers of our memories and as proof of a moment’s transience, they can unfold their impact on the viewer in the sense described by Barthes. Roland Barthes speaks of “it has been” (ça a été), emphasizing the evidential character of photography – the image as testimony that something truly existed. This process of transferring an image from the digital to the material realm is part of that magic. In this way, the image becomes an integral part of reality, one that cannot be fully captured in the digital world.