Heliography Project 1827-2027

The Beginning

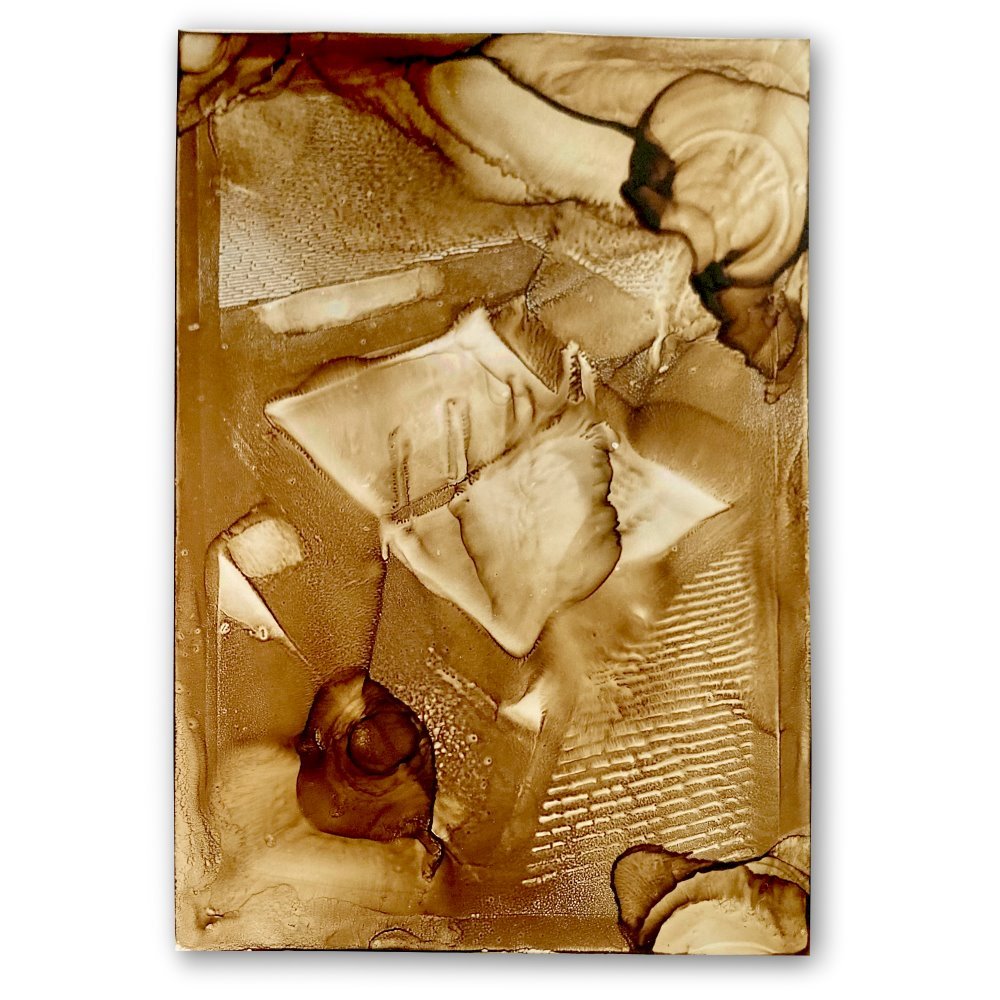

In 1827, Joseph Nicéphore Niépce exposed a pewter plate to light over the course of several days, capturing the view from his window—a heliograph, drawn by sunlight: the world’s first permanent photograph. This moment marked the beginning of an era in which light became testimony—a material proof of lived time. Two hundred years later, in the digital age, this notion is beginning to dissolve.

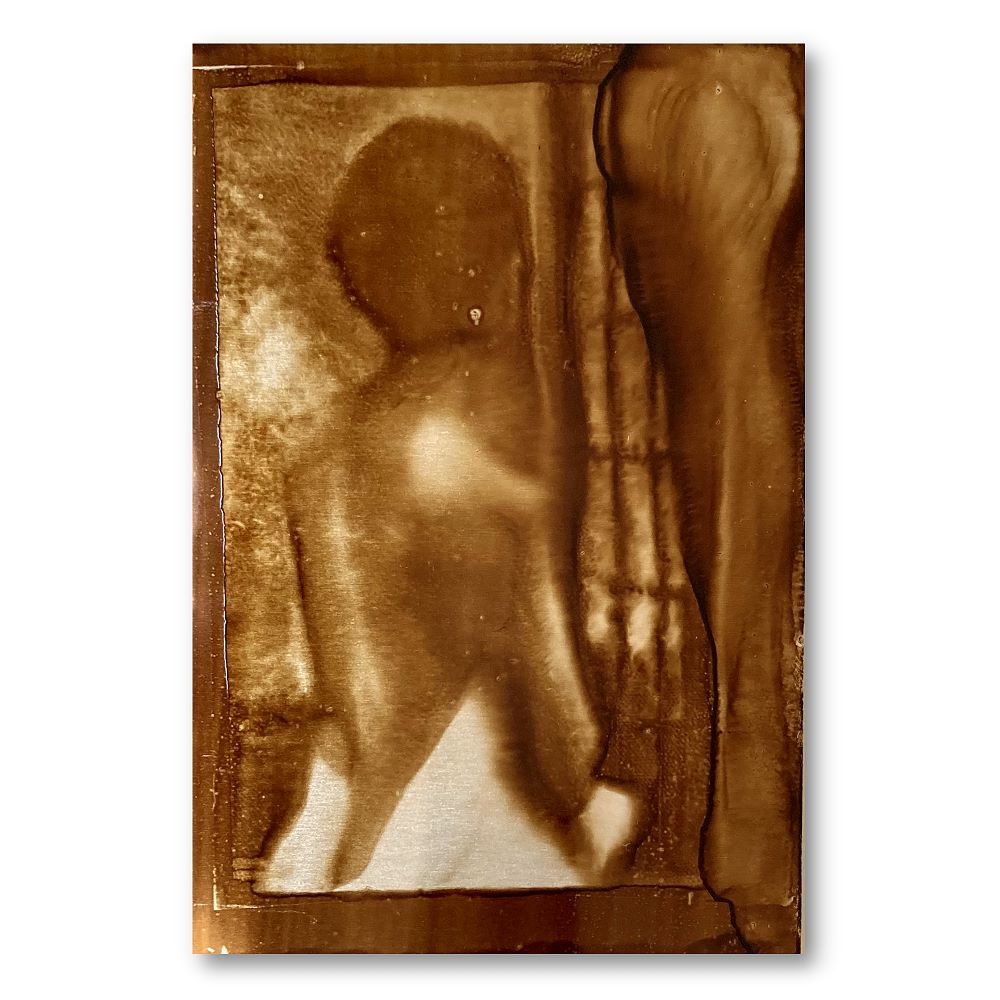

Today, images are created in real time and in unimaginable quantities. Cameras mounted on Google cars, drones, and backpacks systematically capture the world. The technology behind Google Street View documents our everyday lives — emotionless, automated, seemingly objective. Yet it is precisely these images, fleeting and algorithmically generated, that reveal something about our present. They show people in passing, glances at phones, waiting bodies, random shadows — fragments of a daily life never meant for eternity.

I intervene in this digital archive, extract fragments, and bring them back into the material world using the technique of heliography. This retranslation is, for me, a gesture of resistance — against forgetting, against the fleeting surface of digital images. For only in physical form, exposed to aging, touch, and light, can an image unfold its original power.

-

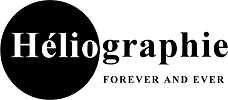

Heliography, Midday in Paris, August 2013, 17 Rue Beaubourg (sold out)

-

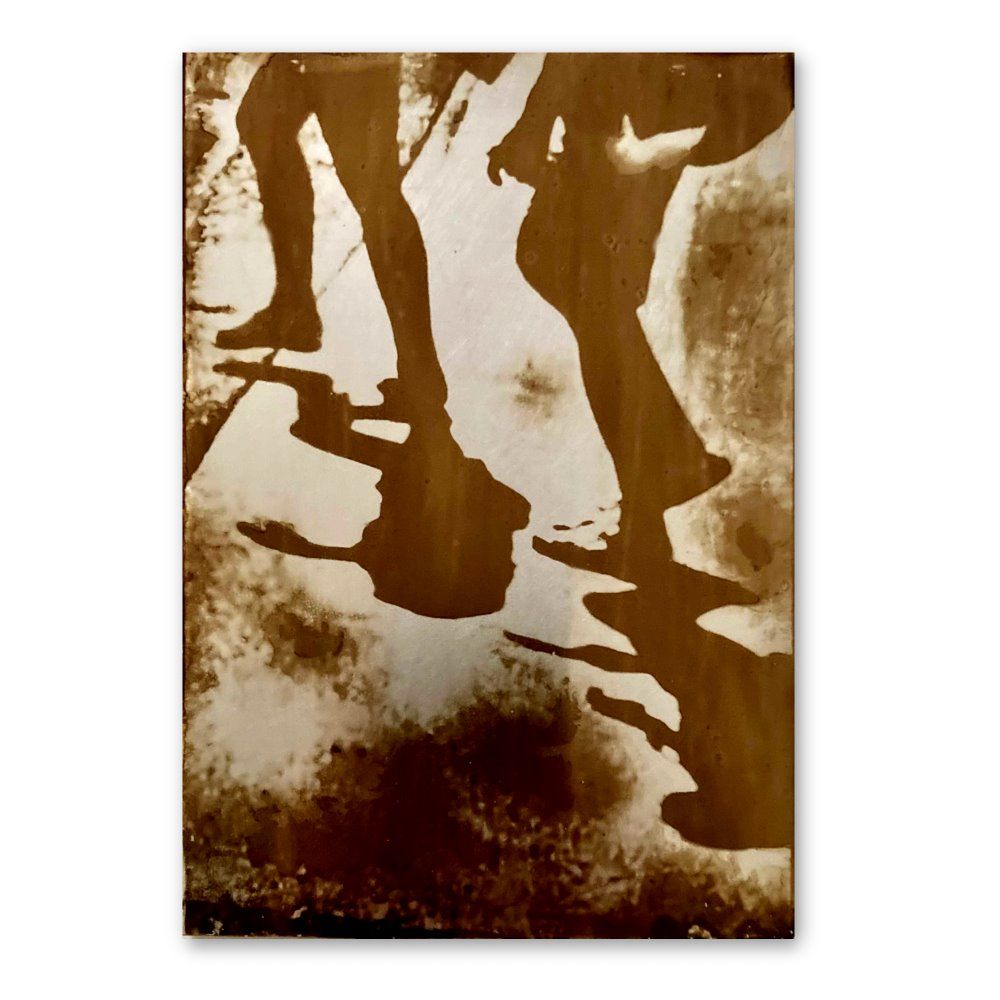

Heliography, Seven Roses for M. – Summer 2017 – the second Rose, Unique

159,00 € -

Heliography, Seven Roses for M. – Summer 2017 – the first Rose, Unique

159,00 € -

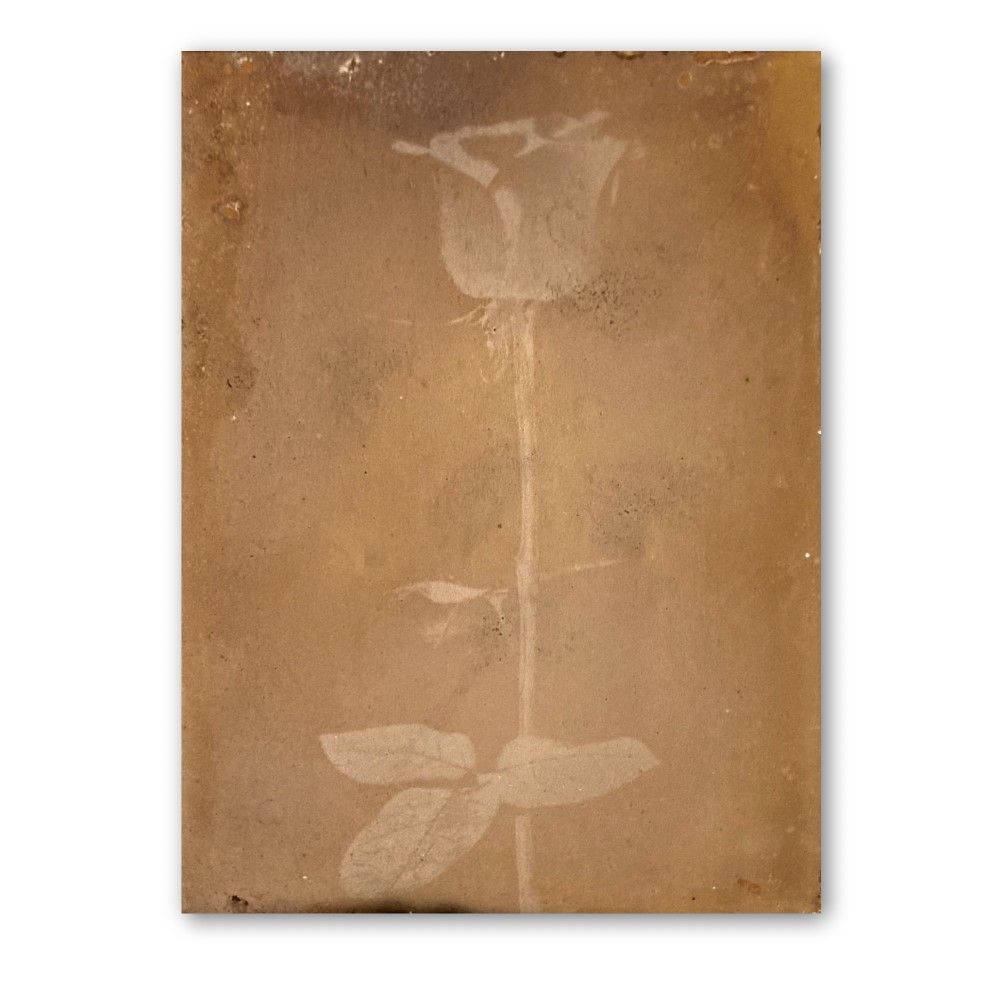

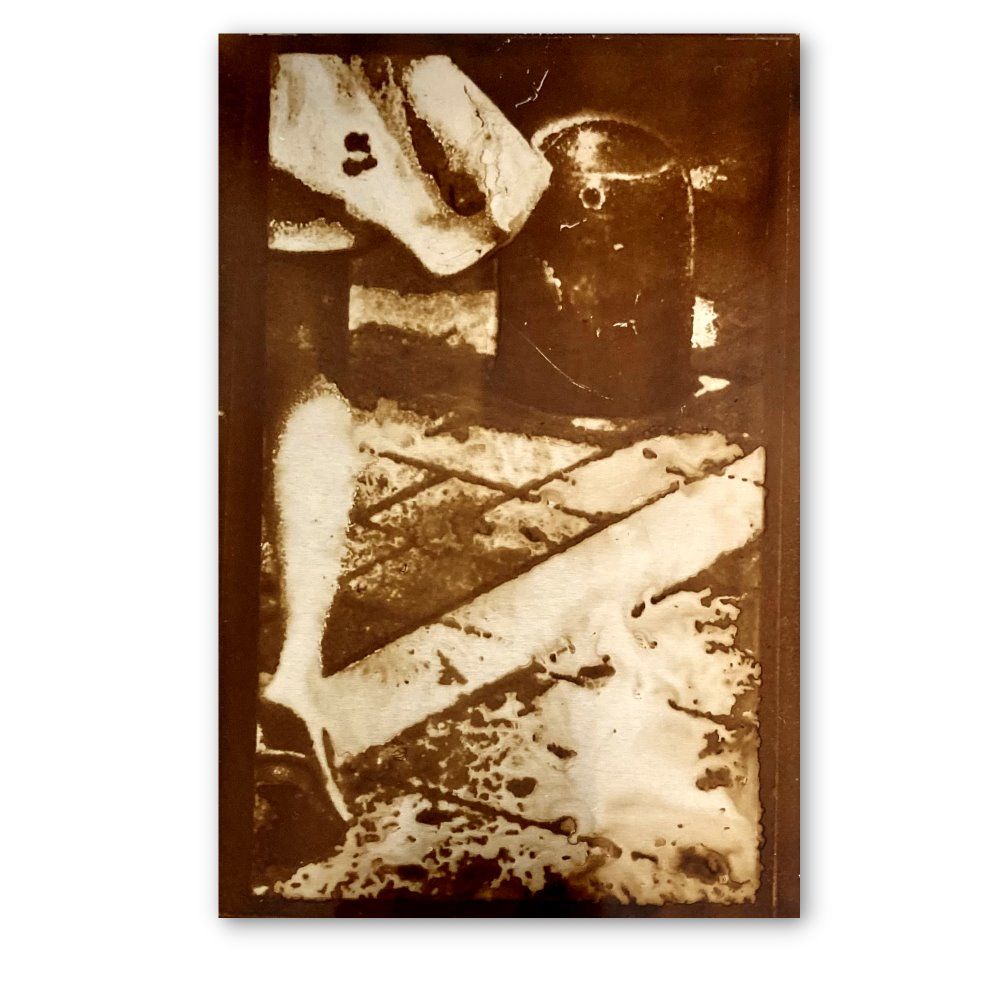

Heliography, Still Life with a Photograph

159,00 € -

Heliography, Somewhere in Paris – in the summer of 2019

159,00 € -

Heliography, Somewhere in Paris – in the summer of 2017 (sold out)

-

Heliography, die Verwandlung, Unique

159,00 € -

Heliography, The Embrace

159,00 € -

Heliography, The Clock

159,00 € -

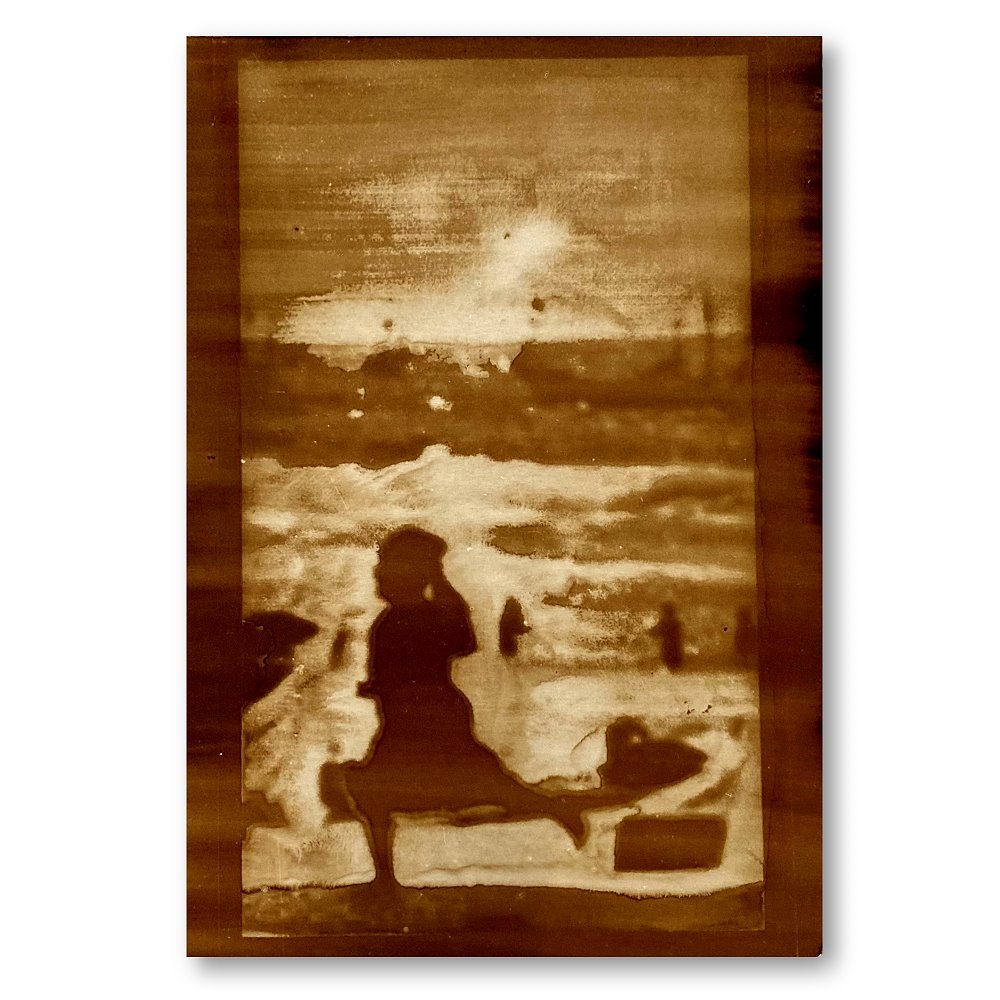

Heliography, The Shadow and the Girl (sold out)

-

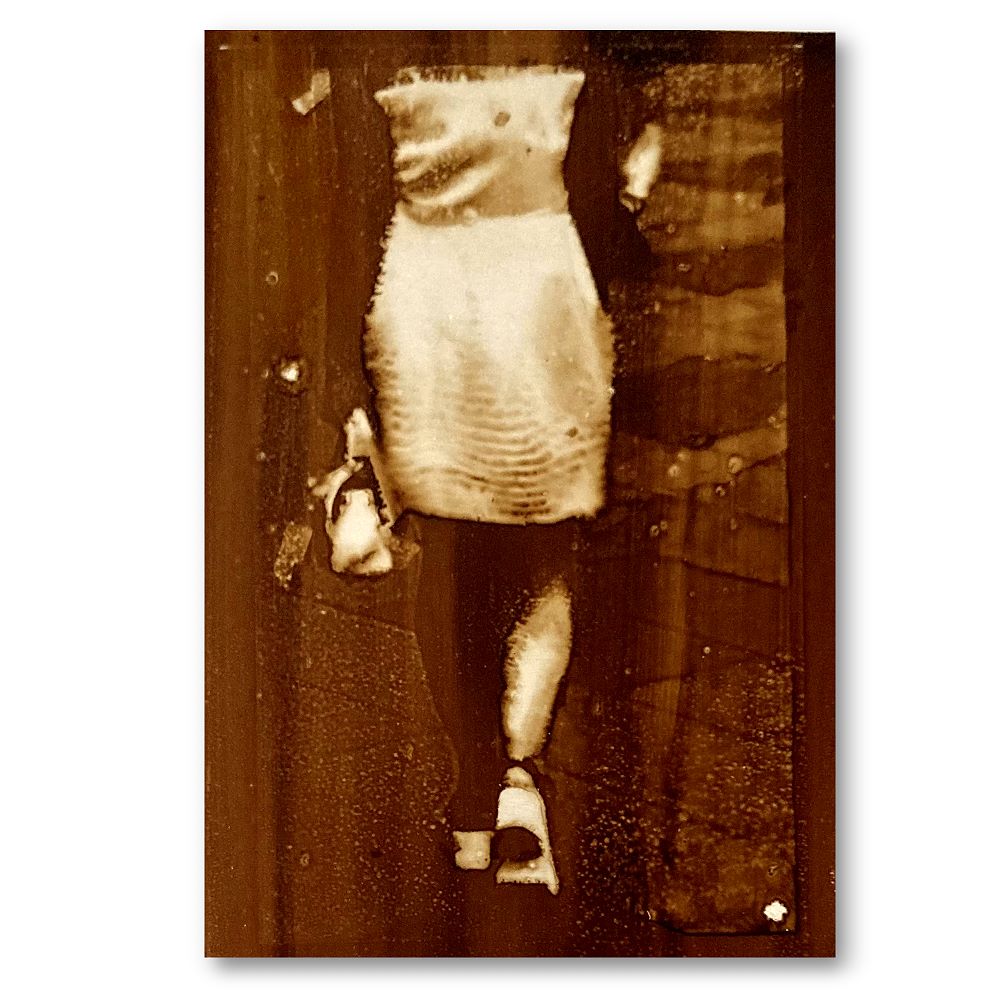

Heliography, The Dress

159,00 € -

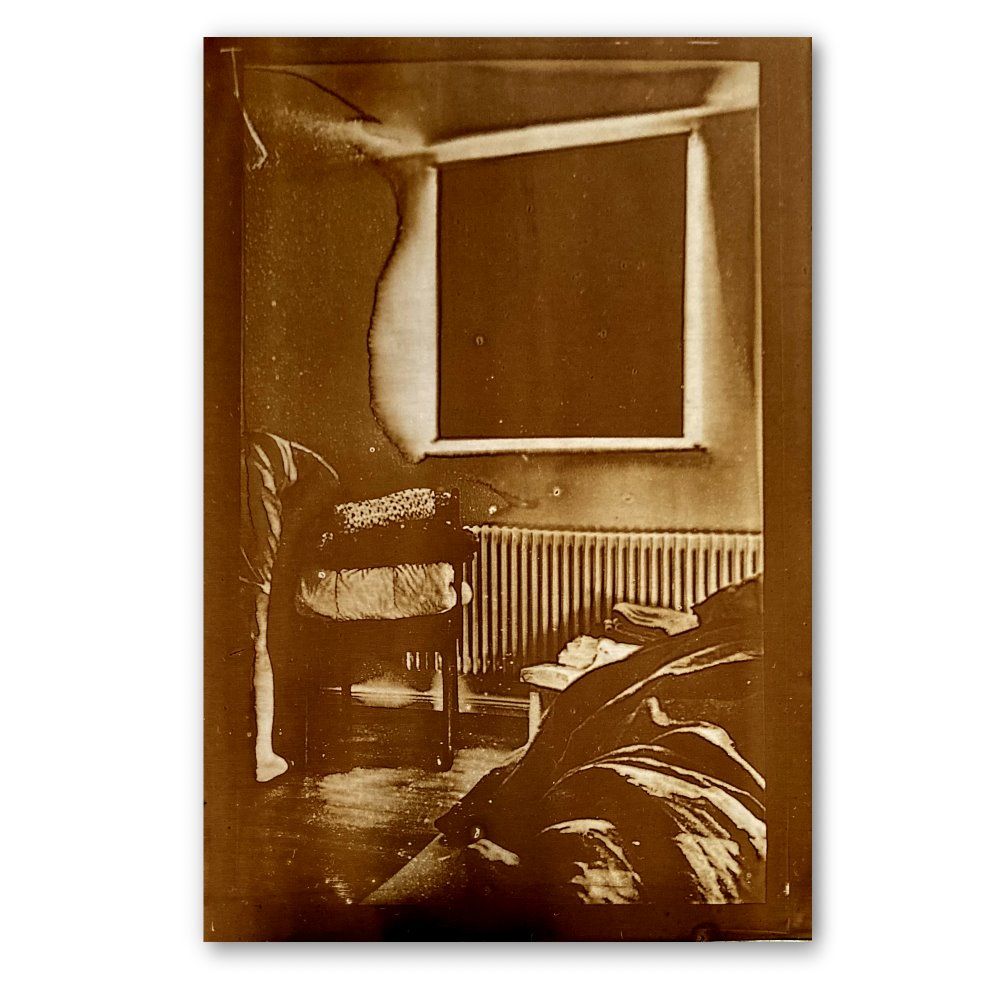

Heliography, The Window

159,00 € -

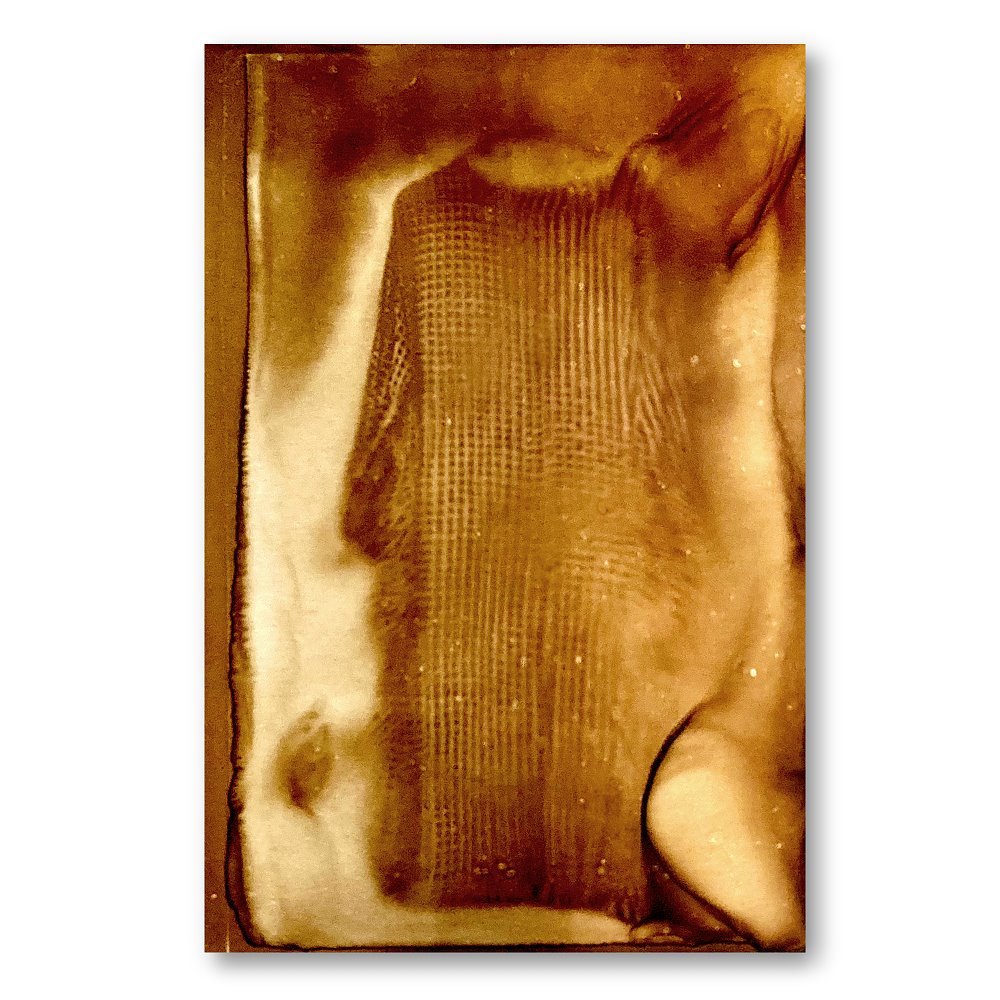

Heliography, The book

159,00 € -

Heliography, Woman with bag (sold out)

-

Heliography, Fear

159,00 € -

Heliography, at the window

159,00 € -

Heliography, The Dress

159,00 € -

Heliography, The Wanderer, Shibuya, Tokio, Mai 2015

159,00 € -

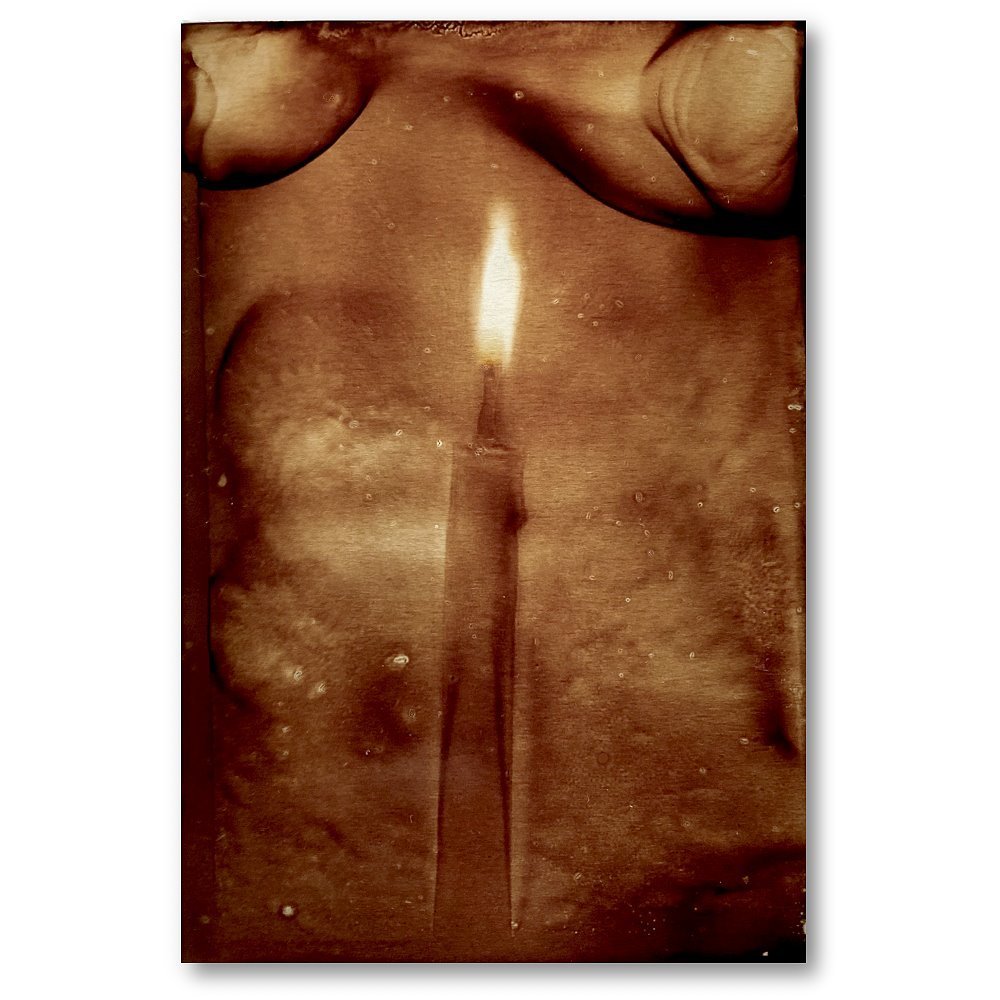

Heliography, Candle

159,00 € -

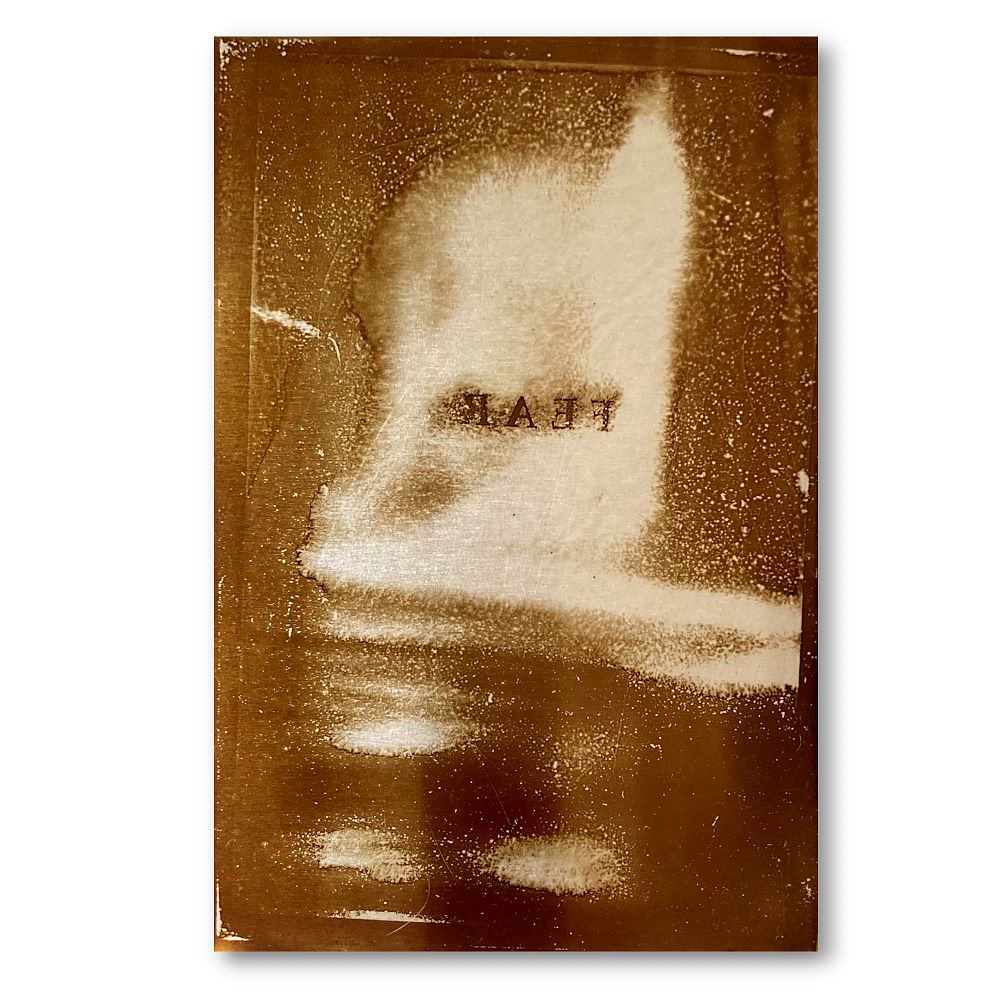

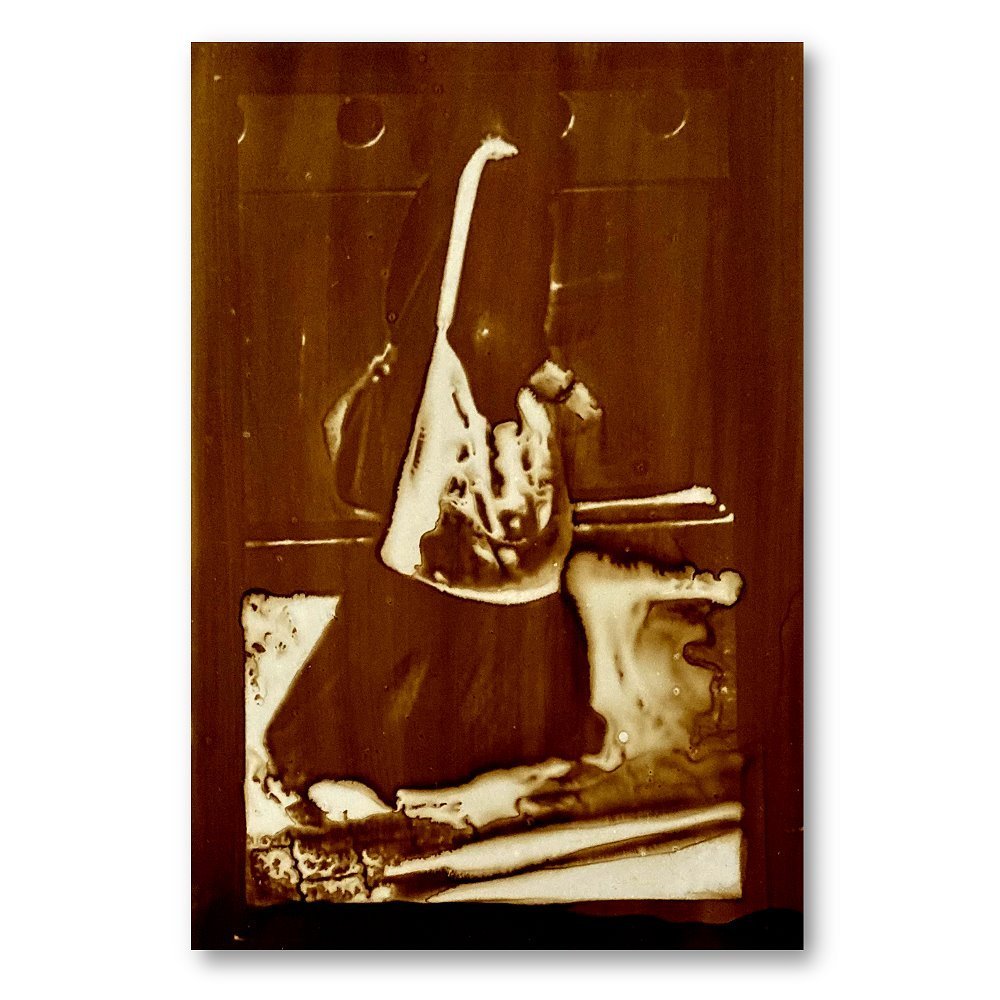

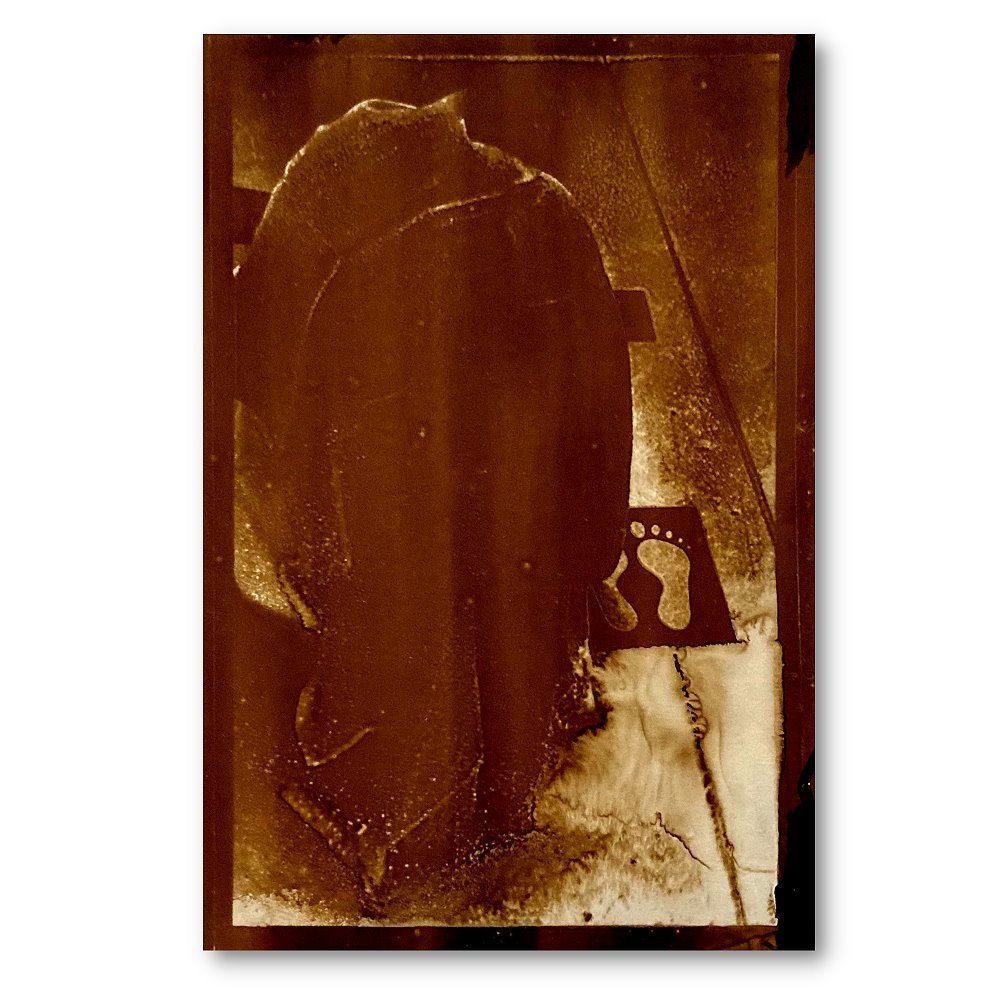

Heliography, Orwell 1984

159,00 € -

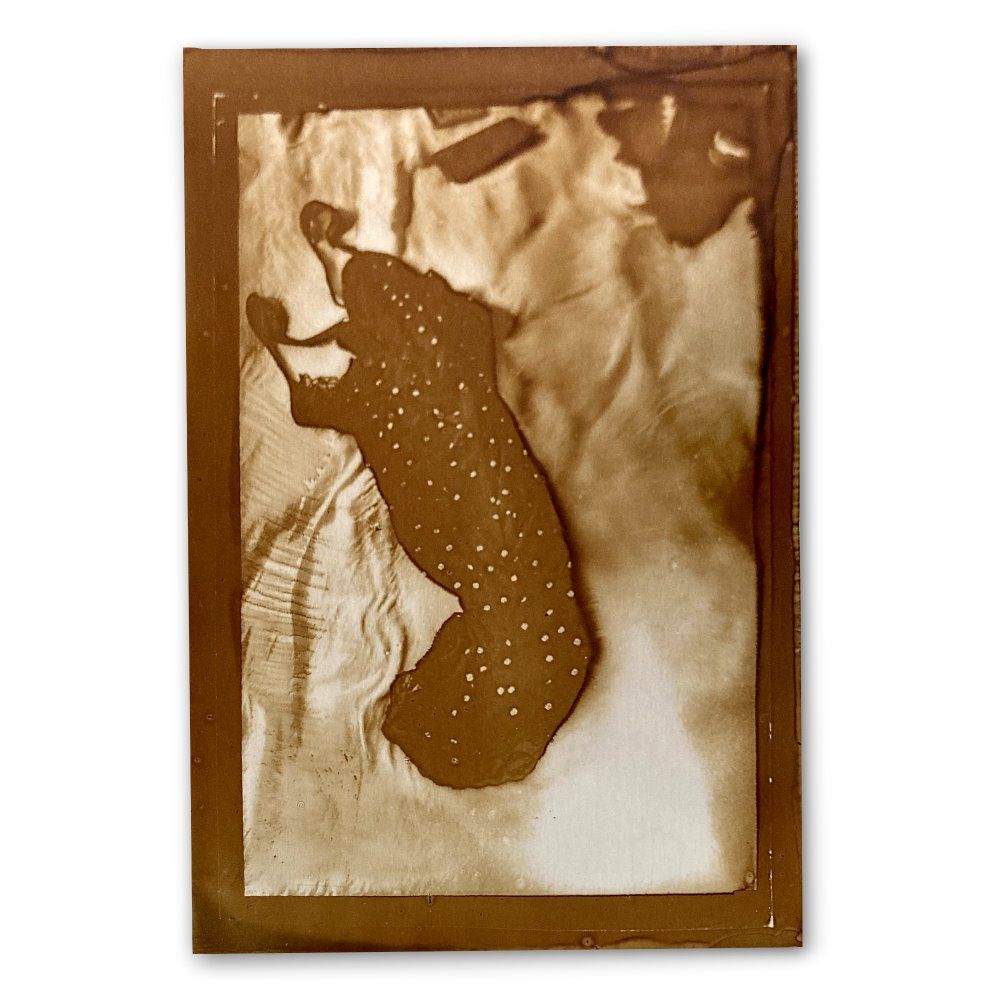

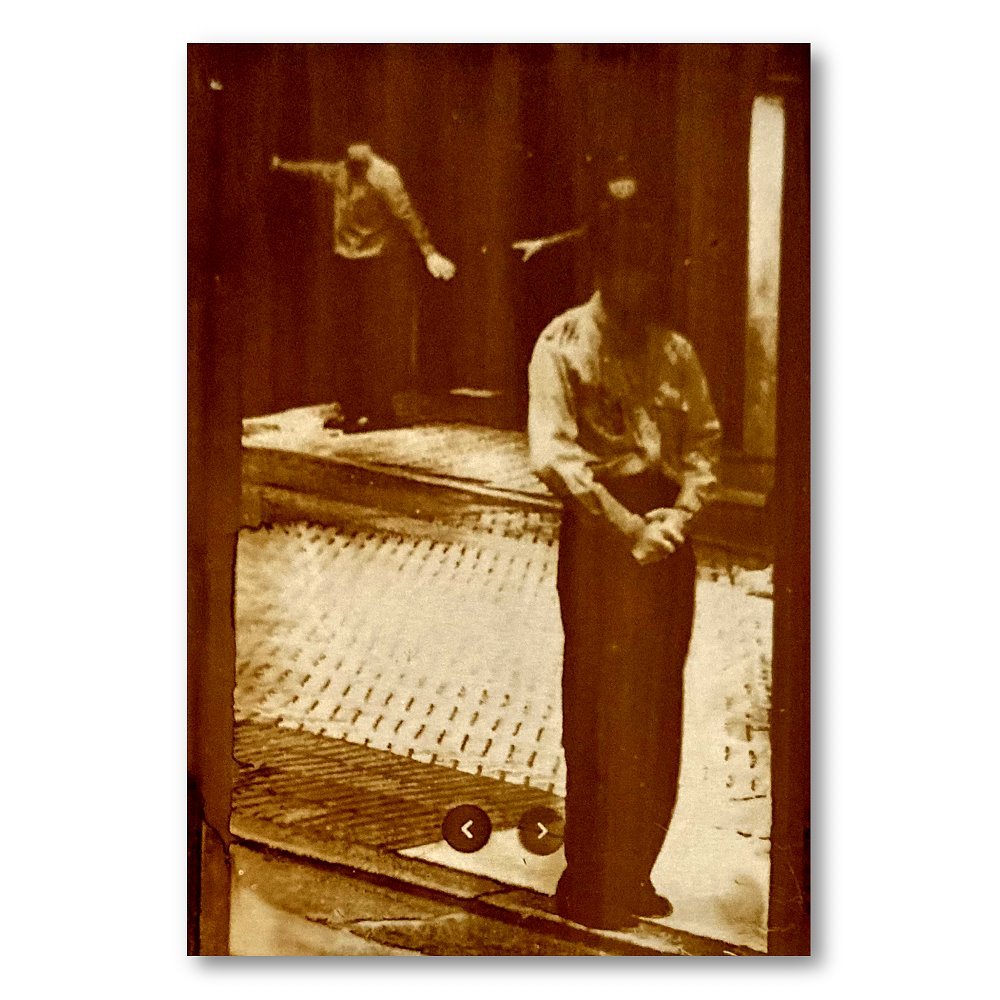

Heliography, Beginning

159,00 € -

Heliography, Coffee in Bed

159,00 € -

Heliography, I hear the Sound of the Sea (sold out)

-

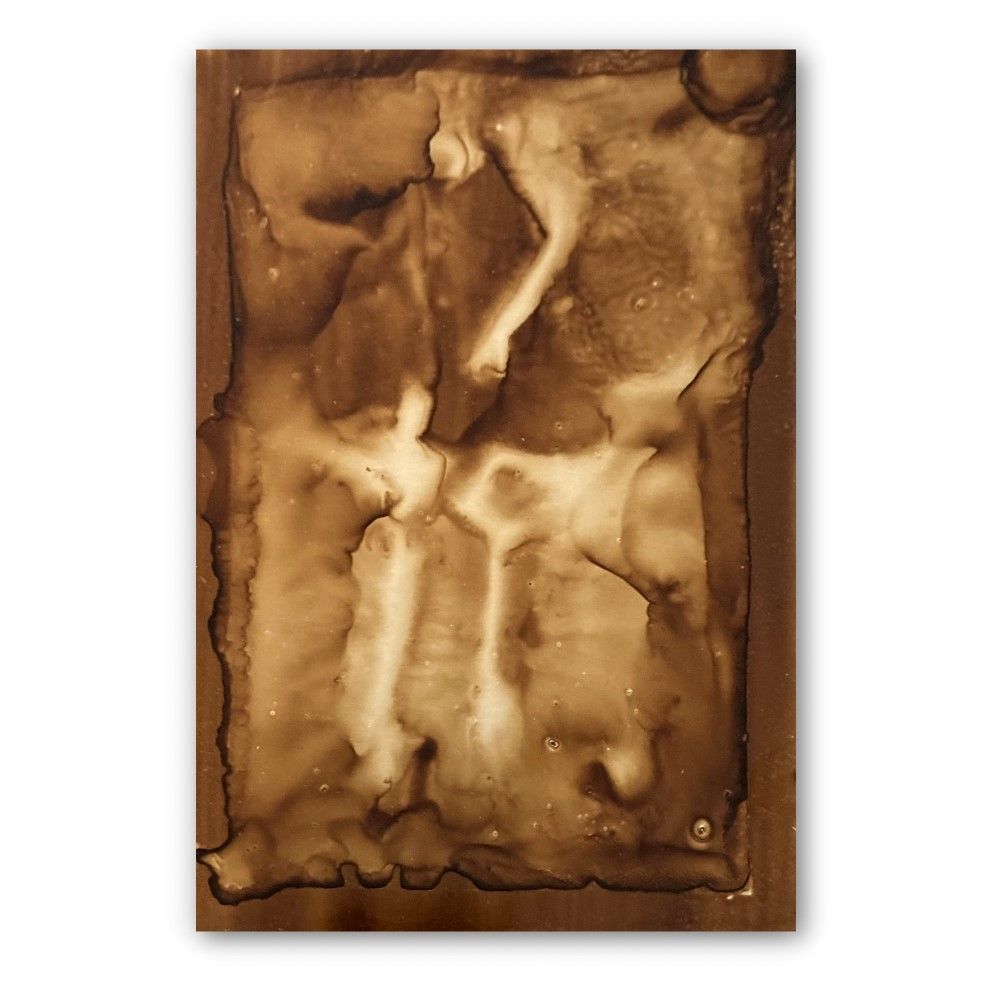

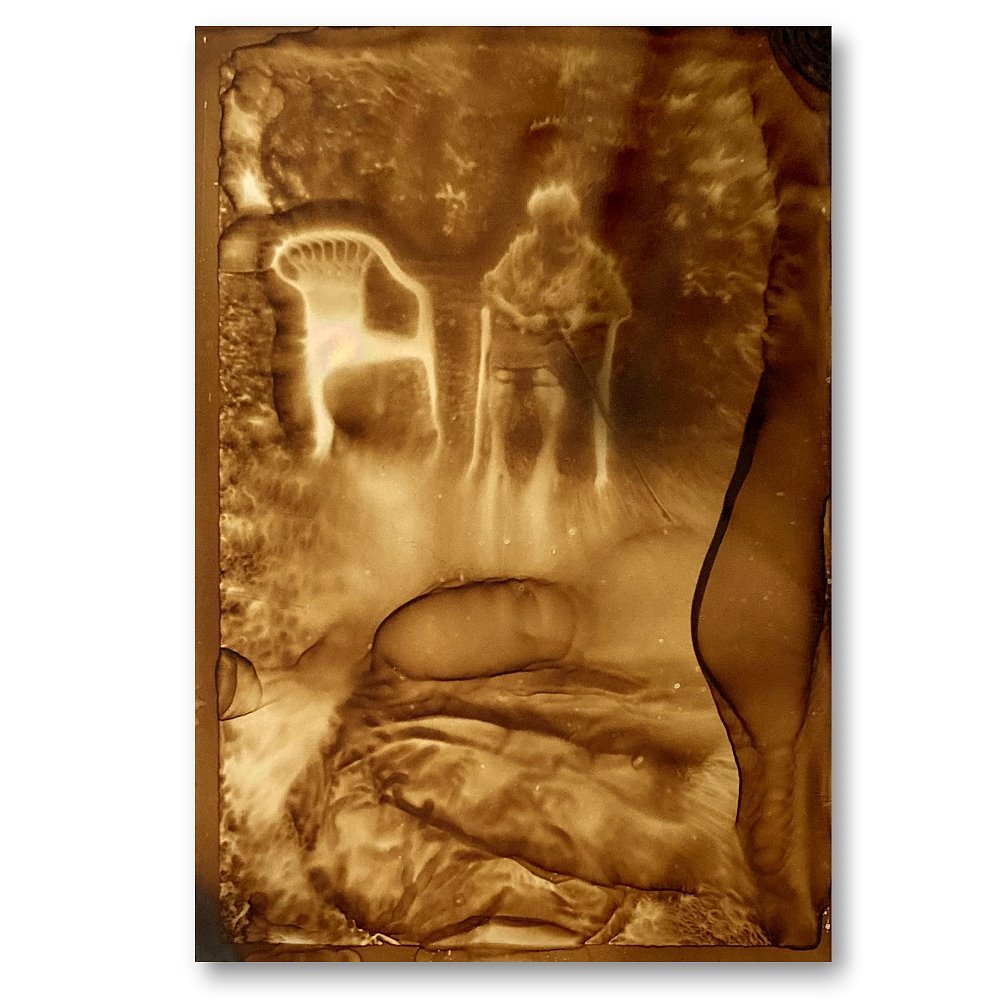

Heliography, Prayer

159,00 € -

Heliography, Mother, August, 2023 (sold out)